The Tradition

Five centuries after the Buddha, the noble heritage of Vipassana had disappeared from India. The purity of the teaching was lost elsewhere as well. In the country of Myanmar, however, it was preserved by a chain of devoted teachers. From generation to generation, over two thousand years, this dedicated lineage transmitted the technique in its pristine purity.

Ven Ledi Sayadaw (1846–1923)

Saya Thetgyi (1873–1945)

Sayagyi U Ba Khin (1899–1971)

Shri S. N. Goenka (1924–2013)

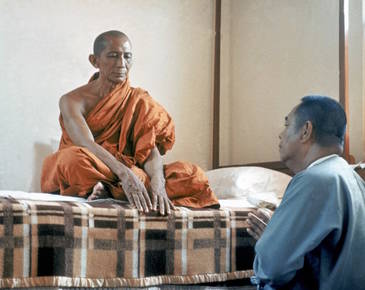

Venerable Webu Sayadaw (1896 - 1977)

Venerable Webu Sayadaw was one of the most highly respected monks of this century in Burma. In 1941, a incident leaded Sayagyi U Ba Khin to meet with Webu Sayadaw and became a watershed for Sayagyi to start sharing Vipassana with others.

Venerable Webu Sayadaw was one of the most highly respected monks of this century in Burma. (Sayadaw is a title used for monks. It means "respected teacher monk.") He was notable in giving all importance to diligent practice rather than to scholastic achievement. Webu Sayadaw was born in the village of Ingyinpin in upper Burma on 17 February 1896. He underwent the usual monk's training in the Pali scriptures from the age of nine, when he became a novice, until he was twenty-seven. In 1923 (seven years after his ordination), he left the monastery and spent four years in solitude. He practiced (and later taught) the technique of Anapana-sati (awareness of the in-breath and out-breath). He said that by working with this practice to a very deep level of concentration, one is able to develop Vipassana (insight) into the essential characteristics of all experience: anicca (impermanence), anatta (egolessness) and dukkha (unsatisfactoriness). Webu Sayadaw was famous for his unflagging diligence in meditation and for spending most of his time in solitude. He was reputed to be an arahant (fully enlightened one), and it is said that he never slept.

For the first fifty-seven years of his life, Webu Sayadaw stayed in upper Burma, dividing his time among three meditation centres in a small area. After his first trip to Rangoon, at the invitation of Sayagyi U Ba Khin, in 1953, he included southern Burma in his travels, visiting there to teach and meditate from time to time. He also went on pilgrimage to India and Sri Lanka. Webu Sayadaw spent his final days at the meditation centre in the village where he was born. He passed away on 26 June 1977, at the age of eighty-one. The following describes Sayagyi's first meeting and subsequent contact with this noble person. At the beginning of 1941, U Ba Khin had been promoted to the post of Chief Accounts Officer, Burma Railways Board. One of his duties was to travel on the Rangoon-Mandalay line auditing the accounts of local stations. He travelled in a special carriage for the Chief Accountant, with full facilities for office work and sleeping overnight. His carriage would be attached to the main train, then detached at various stations.

One day in July, by error his carriage was detached at a station in the town of Kyaukse, forty miles south of Mandalay. Although he was not scheduled to audit the accounts here, as Accounts Officer he was permitted to check the accounts of any station, and he proceeded to do this. After his work was over, he decided to visit the nearby Shwetharlyaung Hill and set out with the local station master. Sayagyi had heard that a monk named Webu Sayadaw, who had reached a high stage of development, was residing in the area. From the top of the hill they could see a cluster of buildings in the distance. They recognized this as the monastery of Webu Sayadaw and decided to go there. At about 3:00 p.m. they arrived at the compound. An old nun sat pounding chillies and beans, and they asked her if they could pay respects to the Sayadaw. "This is not the time to see the reverend Sayadaw," she said. "He is meditating and will not come out of his hut until about six o'clock. This monk does not entertain people. He only comes out of his hut for about half an hour in the evening. If there are people here at this time, he may give a discourse and then return to his hut. He will not meet people at times they may wish to meet him." U Ba Khin explained that he was a visitor from Rangoon and that he did not have much time. He would like very much to meet Webu Sayadaw. Would it not be possible to pay respects outside? The nun pointed out the hut, a small bamboo structure, and the visitors went there together.

Sayagyi knelt on the ground and said, "Venerable Sir, I have come all the way from lower Burma, Rangoon, and wish to pay respects to you." To everyone's astonishment, the door to the hut opened and the Sayadaw emerged, preceded by a cloud of mosquitoes. Sayagyi paid respects, keeping his attention in the body with awareness of anicca. "What is your aspiration, layman?" Webu Sayadaw asked Sayagyi. "My aspiration is to attain nibbana, sir," U Ba Khin replied. "Nibbana? How are you going to attain nibbana?" "Through meditation and by knowing anicca, sir," said Sayagyi. "Where did you learn to be aware of this anicca?" Sayagyi explained how he had studied Vipassana meditation under Saya Thetgyi. "You have been practicing Vipassana?" "Yes, sir, I am practicing Vipassana." "What sort of Vipassana?" Webu Sayadaw questioned him closely and Sayagyi gave the details. The Sayadaw was very pleased. He said, "I have been meditating in this jungle alone for years in order to experience such stages of Vipassana as you describe." He seemed astonished to encounter a householder who had reached advanced proficiency in the practice without being a monk. Webu Sayadaw meditated with Sayagyi, and after some time said, "You must start teaching now. You have acquired good parami (accumulated merit), and you must teach the Dhamma to others. Do not let people who meet you miss the benefits of receiving this teaching. You must not wait. You must teach–teach now!" With a Dhamma injunction of such strength from this saintly person, U Ba Khin felt he had no choice but to teach. Back at the railway station, the assistant station master became his first student. Sayagyi instructed him in Anapana meditation in his railway carriage, using the two tables of the dining compartment as their seats.

Although Sayagyi did not begin to teach in a formal way until about a decade later, this incident was a watershed. It marked the point at which Sayagyi began to share his knowledge of meditation with others. In 1953, at a time when there was much conflict and strife in lower Burma, some government officials suggested that they should invite some of the saintly monks of the country to visit the capital, Rangoon. There was a traditional belief that if a highly developed person visited in a time of trouble, it would have a beneficial effect and the disturbances would calm down. Webu Sayadaw was not well-known in Rangoon because prior to this time he had strictly confined his travels to his three meditation compounds at Kyaukse, Shwebo and Ingyinpin, never leaving this small area of northern Burma. Sayagyi, however, felt strongly that this saintly monk should be invited to visit Rangoon. Even though he had not seen nor communicated with Webu Sayadaw since 1941, Sayagyi felt confident that he would accept the invitation, so he sent one of his assistants to upper Burma to ask the Sayadaw to come and visit his centre in Rangoon for one week.

This was during the time of the monsoon retreat when the monks, according to their monastic rules, must spend their time in meditation rather than in travel. Monks are not ordinarily permitted to travel during the monsoon retreat; however, for a special purpose, a monk may leave his retreat for up to seven days. When U Ba Khin's messenger reached Mandalay and people heard what his mission was, they scoffed. "Webu Sayadaw never travels," they told him. "Especially not now during the rainy season. He will not go out for even one night, let alone seven days. You are wasting your time." Nevertheless, Sayagyi had sent him on this errand, so he persevered. He hired a taxi to Shwebo and sought an audience with the Ven. Sayadaw. When the assistant told Webu Sayadaw that he had been sent by Sayagyi U Ba Khin and extended Sayagyi's invitation, the monk exclaimed, "Yes, I am ready. Let us go." This response was a great surprise to everyone.

Webu Sayadaw, accompanied by some of the monks from his monastery, then paid a visit to the International Meditation Centre. This visit, coming after more than a decade since the two men had first met, demonstrated Webu Sayadaw's high regard for Sayagyi. Moreover, it was unusual for a monk to stay at the meditation centre of a lay teacher. Between the years of 1954 and his death in 1977, Webu Sayadaw made regular annual visits to towns in southern Burma to teach Dhamma. During Sayagyi's lifetime, he periodically visited I.M.C. as well. The Sayadaw was held to have attained high attainments in meditation, and it was a great honour for I.M.C. to receive him. When Webu Sayadaw visited Sayagyi's centre, he usually gave a short Dhamma talk every day. He once mentioned, "When we first visited this place it was like a jungle, but now what progress has been made in these years. It resembles the time of the Buddha when many benefited! Can one count the number? Innumerable!" At one time, Sayagyi decided to fulfill the Burmese tradition of becoming a monk at least once in one's lifetime. Without notifying anyone in advance, he and one of his close disciples, U Ko Lay (the ex-Vice-chancellor of Mandalay University) went to Webu Sayadaw's centre at Shwebo and, under the Sayadaw's guidance, took robes for a period of about ten days.

After Sayagyi's death, Webu Sayadaw visited Rangoon and gave a private interview to about twenty-five students from Sayagyi's centre. When it was reported to him that Sayagyi had died, he said, "Your Sayagyi never died. A person like your Sayagyi will not die. You may not see him now, but his teaching lives on. Not like some persons who, even though they are alive, are as if dead–who serve no purpose and who benefit none."